“If you get shot, what am I going to say to Janette and the kids?”

The question came from Grahame Morris, John Howard’s close friend and trusted advisor in June of 1996. It led him to one of the very few decisions of his prime ministership that he would deeply regret.

Mr Howard had been Prime Minister less than 50 days when the country was rocked by an act of mass madness by one man in Tasmania, one that remains the fifth worst gun massacre by a single individual anywhere in the world.

Thirty-five people were killed in Port Arthur, many of them shot at point blank range. Twenty-one were injured.

Within a week, Mr Howard’s cabinet had agreed to the most far-reaching gun reforms in the country’s history, including a total ban on the ownership, sale, possession and importation of automatic and semi-automatic weapons.

A few weeks later, State and federal police ministers approved the unprecedented crackdown on guns, including a buyback scheme that would reduce Australia’s estimated stock of firearms by one fifth. Then the backlash began.

Some MPs in regional seats received letters with white feathers to symbolise cowardice, or black targets on a clean sheet of paper. One Queensland MP had a grave dug in the block next door to his home. Another, Bill Taylor, broke down in Parliament while describing the death threats he had received.

Mr Howard’s purpose in going to Gippsland was to explain the decision to people who opposed it, most of them traditional Coalition voters who considered themselves upstanding, law-abiding citizens and believed they were now being treated like would-be criminals.

Within two hours of his scheduled appearance at the Sale football ground, Federal Police informed Mr Howard they had been told of a threat to assassinate the Prime Minister and believed it was serious.

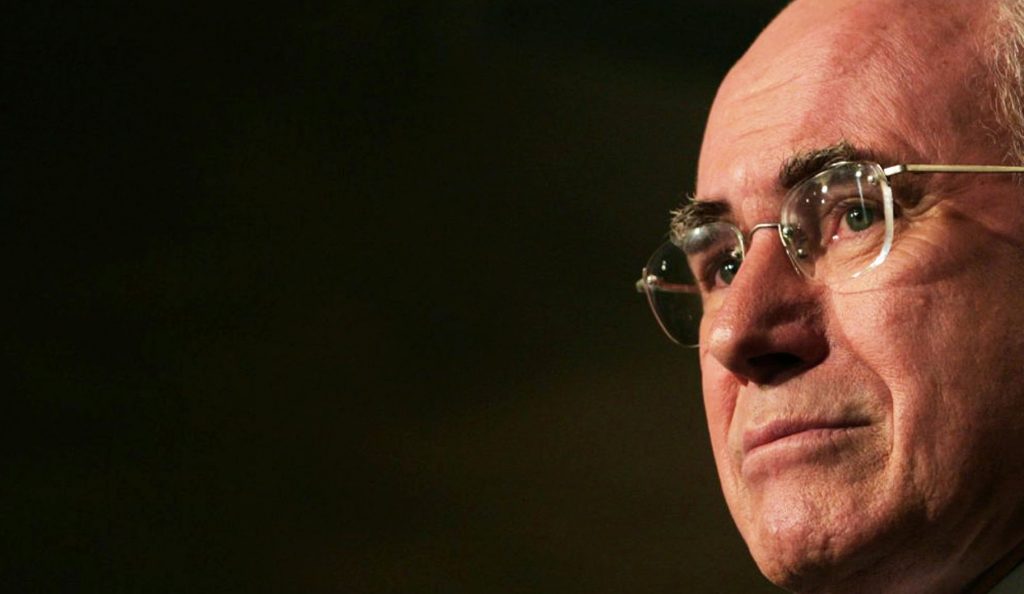

\John Howard, wearing a protective vest, as he addressed gun owners in Sale, 1996. Picture: Colin Murty/Fairfax Media

Their preference was for Mr Howard to cancel the appearance or, if that was not possible, to become the first Australian prime minister to wear a bullet proof vest on home soil.

“I can’t. It’s terrible. I don’t want to wear a vest. I’ve never felt physically unsafe,” he recalls replying. “I didn’t think anybody was going to shoot me. I just didn’t imagine it.”

The police then approached Mr Morris, stressing the gravity of the threat and imploring him to convince Mr Howard to wear the vest. Aside from asking what he would say to Mr Howard’s wife and three children, Mr Morris said it would inevitably emerge that Mr Howard had ignored the warning.

The Prime Minister succumbed.

Unfortunately for him, the vest proved very difficult to conceal under his tweed jacket and it was obvious in a photograph taken from behind that featured on the front pages of newspapers across the country the next morning. One carried an editorial asserting Australia had “reached a confronting milestone”.

“It was probably Grahame’s advice in the end that did the trick, but I don’t hold it against him,” Mr Howard says now. “Probably, if I’d been a little older in the job, I would have relied entirely on my instincts.”

As it happened, the Sale appearance was free of physical violence, although a fringe element within the 3,000-strong crowd punctuated Mr Howard’s 90-minute appearance, most of it patiently answering questions from farmers, with Nazi salutes and chants of “Sieg Heil”.

After the speech, Mr Howard did leave the grandstand to mingle with the crowd and recalls that he did not feel uncomfortable. He adds that not once in his political career did he ever feel fearful or physically threatened.

“I never thought someone was going to do violence, somebody was going to try and shoot me or kill me. I never thought that,” he explains. “I didn’t think there were Lee Harvey Oswalds stalking meetings I went to.”

The episode is a footnote in a case study in political leadership, one that demonstrated policy ambition, courage, a capacity to build consensus and empathy, almost in equal measure.

Mr Howard agreed to discuss his response to the massacre and his approach to leadership as he prepares to join Julia Gillard, another former prime minister, and others in judging what may well be Australia’s first national award for political leadership, the McKinnon Prize.

At a time when perceptions of political leadership are at an historical low, the chair of the selection panel, University of Melbourne Vice Chancellor Glyn Davis, says the aim of the prize is to recognise those leaders who have driven change and, in the process, encouraged a positive national discussion about the role of politicians and leadership.

Two recipients, an established politician and one with less than five years’ experience, will be announced in March.

Mr Howard did accept the advice of the security experts when it came to his appearance at Sale, but he rejected the assessment senior bureaucrats and colleagues when it came to the policy itself.

In his biography, John Howard, Lazarus Rising, Mr Howard recalls how his Attorney-General, Daryl Williams, reported that it was “all a little too difficult” after meeting with state police ministers, especially those from Western Australia and Queensland, and how the senior bureaucrat advising him had cautioned that what he was seeking was “too ambitious”.

His response was that he had accumulated a huge stockpile of political capital with the landslide victory in the March election, and he was prepared to spend a good portion of it achieving the best possible result.

“This was an enormous tragedy. It had instilled fear into the country. People couldn’t believe that this had happened in Australia and I had this big majority. Now, what’s the point of having a majority if you don’t do something with it?” he explains.

“One thing I’ve known about politics for a long time, is that when you inherit a lot of political capital, you can be certain of one thing, it will deplete. Now, you either deplete it through doing something effective, or you just watch it deplete. Because it will deplete. It’s a law of nature.”

Three days after the tragedy, Mr Howard invited then Opposition leader, Kim Beazley, and the leader of then dominant cross-bench party in the Senate, the Australian Democrats’ Cheryl Kernot, to visit Port Arthur with him.

Both strongly backed the gun reforms, as did the overwhelming majority of the population, but this only served to exacerbate tensions within the Coalition, and made it even harder for Mr Howard secure the support of conservatives in the bush.

The imperative was to build consensus on his own side of politics and with state governments, and Mr Howard pays tribute to then National Party leader, Tim Fischer; Fischer’s deputy, John Anderson and the then Queensland Premier, Rob Borbidge, for the roles they played.

At the time, he scoffed at the suggestion that the new gun laws could be the catalyst for a new political force, and told me in an interview at the time for The Weekend Australian: “I think anyone made nervous by the suggestion of a new political party is very gullible. I regard it as a big joke.”

He has since recognised that the stand he took on guns did contribute to the rise of One Nation. “It wasn’t the major reason, but it was a contributory reason,” he says.

“It was an example of an unfeeling, city-centric (government)…this is how it was represented by some of the One Nation people. ‘Here is this insensitive, out-of- touch, city, particularly Sydney-centric, government taking away our weapons.’ And I understood how they felt.”

After a service at St David’s Cathedral in Hobart on the Wednesday after the murders, Mr Howard met with relatives of victims and many of those who had been first responders, including Dr Bryan Walpole, who was hugged by the Prime Minister after he broke down.

Opposition leader Kim Beazley, Prime Minister John Howard and MP Cheryl Kernot place a wreath at Port Arthur. Picture: Nick Cubbin/Herald Sun

“It’s very important to understand in a situation like that that the worst thing a leader can do is to make the extraordinary grief being suffered by those who have lost somebody dear to them even worse by not doing the most natural thing in the world,” says Mr Howard.

“And the most natural thing in the world is to say you are sorry, look people in the face and, if you think the person you are talking wants a handshake, you shake their hand. If you think they are somebody who wants an embrace, you embrace them.”

There would be several other occasions during his prime ministership that Mr Howard would show empathy to those who had suffered a great loss, most notably after the Bali bombing of October 12 2002, when 88 Australians died and scores were horribly injured when two bombs exploded at Kuta Beach.

Five days after the bombings, Mr Howard gave a speech at a sunset memorial service that captured the nation’s bewilderment and disbelief “that so many young lives with so much before them should have been taken away in such blind fury, hatred and violence”.

Mr Howard had thought about what he wanted to say on the flight to Bali and spoke without a note, not once losing eye contact with the relatives and friends of victims in the audience. It may have been the finest speech of his prime ministership.

Mr Howard says it would be presumptuous for one who served so long to offer a definition of political leadership, but he offers the two principles of leadership he considers most important.

“I think the most important thing is to convey a sense of the attitudes and values and beliefs that you have. People want to know what a leader stands for, what he or she wants to achieve, and that is far and away the most important commodity,” he says.

“I often used to joke that I encountered a lot of people who would say I can’t stand you, but I know what you stand for.”

A second imperative, he says, is to develop a keen appreciation of the relationship you have with the people you immediately lead.

“When you are a political leader, you are dealing with a series of concentric circles. There is the inner group, the cabinet, the parliamentary party, the broader party and the broader community and you have to have a relationship with all of them.”

But the most important group is the parliamentary party, for they are the ones who decide who will be leader.

Asked why political leadership is so much harder now, Mr Howard chooses to recast the query, saying he is not sure whether it is harder or not. The question he prefers to address is why is there a greater incidence of insecurity of tenure for leaders, and he suggests three possibilities.

The first is that there is a cyclical dimension to the phenomenon of the revolving door, that we have seen all this before. “Think of (Sir Robert) Menzies,” he says, who was Prime Minister from 1949 until to January 1966. “Then, from January ‘66 to January ‘76 we had (Harold) Holt who drowned, then (John) Gorton, then (Sir William) McMahon, then (Gough) Whitlam, then (Malcolm) Fraser.” Something similar happened in Britain.

A second factor that distinguishes this period is the number of parliamentarians whose dominant life experience has been working in political machines who, as a consequence, “have a rather more cavalier view to leadership changes”.

A life-long fascination with leadership in all its dimensions, drew Mr Howard to agree to be on the McKinnon Prize judging panel; that, and a regard for the work of University of Melbourne Vice Chancellor Glyn Davis. Mr Howard says he was also impressed that the selection panel reflects “a broad cross-section of citizenry”.

Aside from Ms Gillard, the panel includes former Australian cricket captain, Adam Gilchrist; BHP Billiton chief executive, Andrew Mackenzie; one of the country’s most respected public servants, Dennis Richardson; Oxfam chief, Dr Helen Szoke; and constitutional lawyer, Professor Megan Davis.

“I think it’s good that that there’s a former Labor Prime Minister in the group. Things of this nature need to be bipartisan because no one side of politics can ever have a monopoly on government,” says Mr Howard.